In North America, a horse with a colorful spotted coat pattern was developed in the Pacific Northwest by the Nez Perce people. Settlers referred to this horse as the “Palouse Horse”, after the Palouse River in the area. Gradually, this breed’s name evolved into “Appaloosa”.

Artwork depicting prehistoric horses with leopard spotting exists in cave paintings in Europe. Images of domesticated horses with the same coloring patterns appear in artwork from Ancient Greece and Han dynasty China through to modern times. The Nez Perce people of the Pacific Northwest United States lost most of their horses after the Nez Perce War in the year 1877. The Appaloosa breed fell into decline for several decades after this. Because of the dedication of a small number of breeders, the Appaloosa was preserved as a distinct breed until the Appaloosa Horse Club (known as the ApHC) was formed in 1938 and acted as a breed registry. The modern breed maintains bloodlines tracing back to the foundation stock of the registry. The breed registry allows some addition of Thoroughbred, Quarter Horse, and Arabian blood.

Today, the Appaloosa is one of the most popular breeds in the United States. It was named the official state horse of Idaho in 1975. Appaloosas have been used in movies, as sports team mascots, and as influence to other horse breeds. They are a versatile breed, suitable as a stock horse in western riding disciplines as well as other equestrian activities.

The Appaloosa is best known for its leopard spotted coat, which is the preference in the breed. Aside from spotting, there are three other distinctive core characteristics of the Appaloosa: mottled skin, striped hooves, and white sclera in the eyes. Though all horses show white around the eye if the eye is rolled back, white sclera showing while the eye is in a normal position is a distinctive characteristic seen more in Appaloosas than in other breeds. Occasionally, an Appaloosa horse is born with little or no visible spotting pattern. The ApHC allows for the “regular” registration of horses with mottled skin plus at least one other common characteristic of the breed. There is also a “non-characteristic” registration for horses with two ApHC parents who show no identifiable Appaloosa characteristics.

It is not always easy to predict the color a grown Appaloosa will be when it is born. Patterns sometimes change over the course of the horse’s lifetime, and foals do not always show classic leopard spotting characteristics. Horses with the varnish roan and the snowflake patterns usually show very little of the color pattern at birth, but develop more visible spotting as they age. Appaloosa horses come in several base colors, including bay, black, chestnut, palomino, buckskin, cremello, perlino, roan, gray, dun, and grulla. There are ten different recognized spotting patterns, including spotted, blanket, leopard, snowflake, and mottled markings.

Domestic horses with spotted patterns in artwork have been seen as far back as Ancient Greece, Ancient Persia, and China. Eleventh century France and Twelfth century England paintings also depicted spotted horses. Records indicate that spotted horses were used as coach horses at the court of Louis XIV of France, and in the mid-18th-century there was a huge demand for spotted horses among the nobility and royalty. These horses were used in schools, parades, and other displays. The Spanish obtained spotted horses, likely from trade with Austria and Hungary. These horses then traveled with the Conquistadors and Spanish settlers to the Americas in the early 16th century. A snowflake patterned horse was listed among the 16 horses brought to Mexico by Cortez.

Spotted horses went out of style in Europe in the late 18th century. This caused these horses to be shipped to Mexico, California, and Oregon.

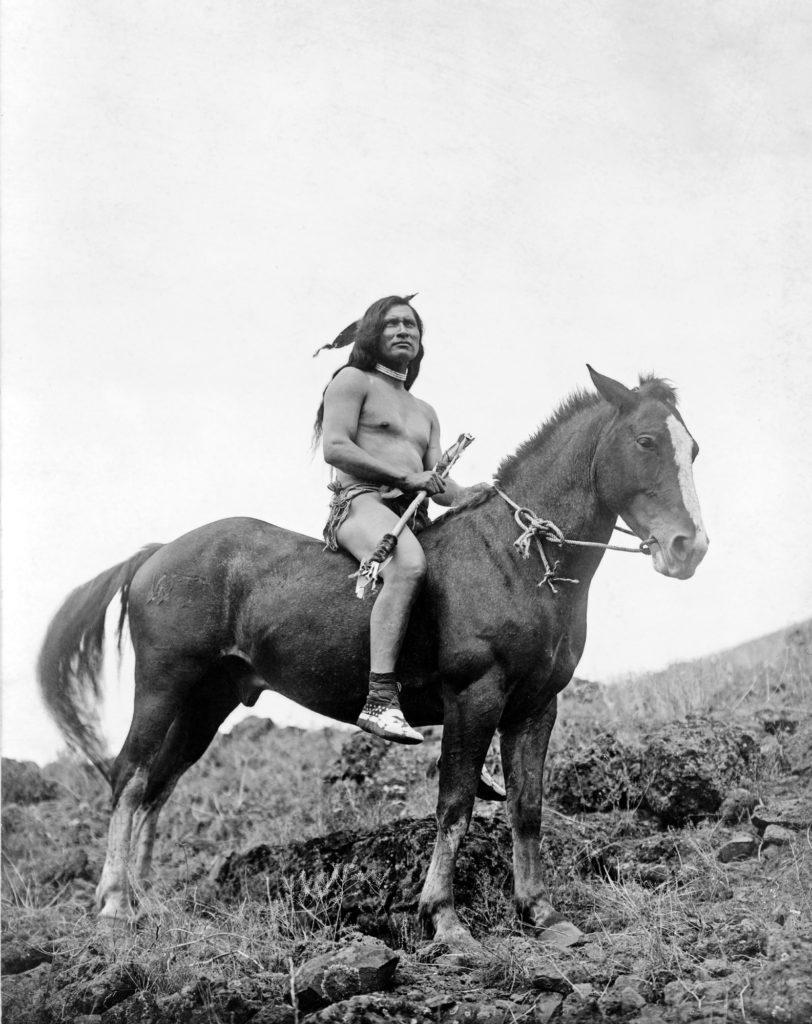

The Nez Perce were living in what is today eastern Washington, Oregon, and north central Idaho. They engaged in horse breeding as well as agriculture. Horses were first obtained by the Nez Perce people in 1730, and they received them from the Shoshone. Because the Nez Perce lived in excellent horse breeding country, and were relatively protected from raids, they took advantage of this and developed strict breeding selection practices. They were one of the few tribes that actively gelded inferior male horses and traded away poor stock to remove unsuitable animals from the gene pool. They were notable horse breeders by the early 19th century.

Nez Perce horses were known to be of the highest quality, and even Meriwether Lewis of the Lewis and Clark Expedition wrote in his journal about the excellence of their horses. He also mentioned the horses being “pied”, noting the spotted patterns of the modern Appaloosa horse. At this time, however, many of the Nez Perce horses were solid colored, as they had not yet begun to breed for color until after Lewis and Clark’s visit. As settlers moved into the Nez Perce lands, the successful trade of their horses enriched the tribe. In 1861, the Nez Perce horses were said to be “elegant chargers, fit to mount a prince.” Ordinary horses at the time could be purchased for $15. Settlers and non-Natives who owned Appaloosa horses from the Nez Perce turned down offers as high as $600 for their animals.

The encroachment of gold miners in the 1860’s and settlers in the 1870’s put pressure on the Nez Perce people. A treaty in 1863 reduced the lands allotted to the Nez Perce people by ninety percent. Some of the Nez Perce refused to give up their lands under this treaty, including a band living in the Wallowa Valley of Oregon. Tensions rose, and in May of 1877, General Oliver Otis Howard called a council and ordered the bands to move to the reservation. The leader of the bands, known as Chief Joseph, felt that military resistance would ultimately be futile. But, on the day that the Chief had gathered 600 people in Idaho, a small group of warriors staged an attack on nearby settlers. After several small battles in Idaho, 800 Nez Perce took 2000 head of livestock and fled into Montana before heading southeast and into Yellowstone National Park.

A small number of the Nez Perce warriors held off larger U.S. Army forces in several skirmishes, including a two-day battle in southwestern Montana. After being rebuffed by the Crow Nation when they sought safety there, the Nez Perce headed for Canada. The journey was around 1,400 miles, and all throughout it, the Nez Perce relied on their fast, agile, and hard Appaloosa horses. They stopped to rest near the Bears Paw Mountains in Montana, around 40 miles from the Canadian border. Unknown to them, Colonel Nelson A. Miles had led an infantry-cavalry from Fort Keough in pursuit. After a five day fight, Chief Joseph surrendered. The Nez Perce war was over on October 5, 1877. Most of the war chiefs were dead, and the noncombatants were cold and starving.

The U.S. 7th Cavalry immediately took more than 1,000 of the tribe’s horses when they accepted Chief Joseph’s surrender. They sold what they could and then shot the rest. A significant population of horses were left behind in the Wallowa Valley when the Nez Perce began their retreat, and additional horses escaped or were abandoned on the way. When the Nez Perce were relocated to reservations in north central Idaho, they were allowed to keep few horses and were forced to crossbreed with draft horses in an attempt to create farm horses.

A remnant population of the Appaloosa horses remained after 1877, but they were nearly forgotten as a distinct breed for nearly 60 years. A few of the best horses continued to be bred and used as working ranch horses. Others were used in circuses and shows, such as Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. The name “Appaloosa” came from the Palouse River that ran through the Nez Perce territories. There were several other spellings of the breed’s name, including “Appalucy”, “Opelousa”, and “Apalousey”. By the 1950’s, “Appaloosa” was considered the correct spelling of the name.

Western Horseman magazine published an article in 1937 describing the Appaloosa breed’s history and urging the preservation of the horses. This was when the Appaloosa came to the attention of the general public. The author of the article, Francis D. Haines, had performed extensive research, including traveling with a friend to various Nez Perce villages to collect history and take photographs. The article generated interest in the breed, and was responsible for the founding of the Appaloosa Horse Club by Claude Thompson in 1938. The Appaloosa Museum Foundation was formed in 1975 to preserve the history of the Nez Perce horse. Western Horseman magazine continued to support and promote the breed in subsequent issues.

The Arabian horse played a huge part in the revitalization of the Appaloosa horse, as evidenced by early registration lists that show Arabian-Appaloosa crossbreeds as ten of the first fifteen horses registered with the ApHC. Later, Thoroughbred and Quarter Horse lines were added, as well as crosses from breeds such as the Morgan and Standardbreds. In 1983 the ApHC reduced the number of allowable crosses to three main breeds: Arabian, American Quarter Horse, and the Thoroughbred.

By 1978, the ApHC was the third largest horse registry of light horse breeds. By 2007, more than 670,000 Appaloosas were registered. They are an international organization, with affiliates in Europe, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Mexico, and Israel. The ApHC has 33,000 members as of 2010.

The American Appaloosa Association was founded in 1983 by members of the ApHC who opposed the registration of solid colored horses. Based in Missouri, the AAA had a membership of more than 2,000 as of 2008. Other registries have been created for horses with leopard complex genetics that are not affiliated with ApHC. The ApHC is, by far, the largest Appaloosa horse registry, and it hosts one of the largest breed shows in the world.

The ApHC does not accept horses with draft, pony, Pinto, or Paint breeding. Mature horses must stand at least 14hh while unshod. If a horse has excessive white markings that are not associated with the recognized Appaloosa patterns, it cannot be registered unless a DNA test reveals that both the horse’s parents have ApHC registration.

Unfortunately, Appaloosas have an eightfold greater risk of developing Equine Recurrent Uveitis than all other breeds combined. Up to 25 percent of all horses with ERU may be Appaloosas. If not treated, ERU can lead to blindness. Appaloosas with roan or light colored patterns, little pigment around the eyelids and sparse hair in the mane and tail mark the most at-risk horses for this condition. Researchers believe they have identified a gene region in the Appaloosa that makes the breed more susceptible to the disease.

Some Appaloosas are also at risk for congenital stationary night blindness. CSNB is a disorder that causes a lack of night vision, though day vision is normal. It is an inherited disorder, present from birth, and does not progress over time.

Appaloosas are a versatile and hardy breed. They are used for both Western and English riding disciplines. Western competitors use the Appaloosa for cutting, reining, roping, barrel racing, and pole bending. Barrel racing is known as the Camas Prairie Stump Race in Appaloosa-only competitions, and pole bending is called Nez Perce Stake Race at breed shows. English riding disciplines use Appaloosas for competitions such as eventing, show jumping, and fox hunting. They are common in endurance riding competitions and casual trail riding. Appaloosas are also bred for horse racing and have an active breed racing association promoting the sport. Generally, they are used for middle-distance racing. An Appaloosa holds the all-breed record for the 4.5 furlongs distance, which was set in 1989.

To learn more about the Appaloosa horse, go to the ApHC Official Website.