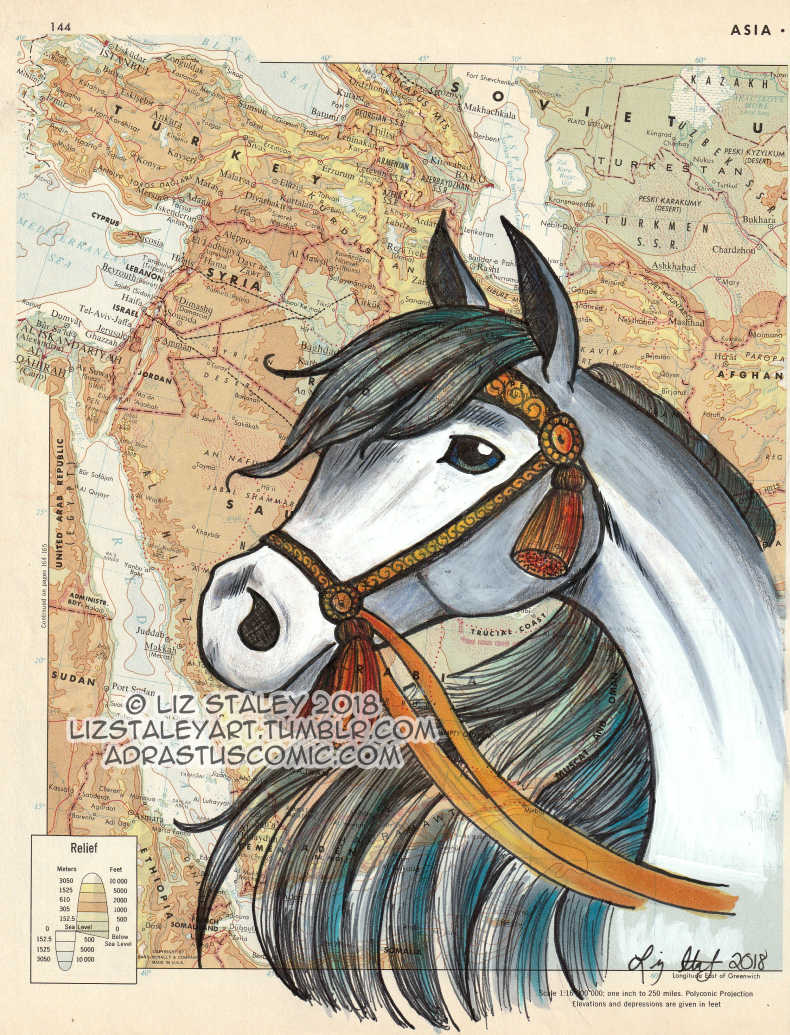

The Arabian horse is one of the oldest horse breeds in the world. Archaeological evidence of horses resembling the Arabian have been found in the Middle East dating back 4,500 years. It is one of the most easily recognizable horses in the world. Throughout history, the Arabian has spread around the world thanks to both war and trade. The breed has been used to improve other horse breeds by adding speed, endurance, and strong bone. The Arabian horse bloodline is found in almost every modern breed of riding horse.

The nomadic Bedouin people of the area where the Arabian developed prized the horses so much that they would often bring them inside the family tent for shelter and to protect the horses from theft. Arabian horses are quick learners, good-natured, and eager to please, with the high spirit and alertness required for war. Arabian horses are the masters of endurance, dominating the sport of endurance riding because of their soundness, strength, and superior stamina. Romantic myths are often told of the Arabian breed, giving them nearly divine characteristics and powers.

There are several myths of the origin of the Arabian horse. One origin myth tells of how Muhammed gave his mares a test of their loyalty and courage by turning them loose after a long journey through the desert and let them race toward an oasis for a desperately needed drink of water. Before the herd reached the oasis, Muhammed called the herd back to him. Only five mares returned to their master, becoming his favorites and being named Al Khamsa– “The Five”. These mares became the legendary foundation mares of the five strains of Arabian horses.

Another version says that Solomon gave a stallion to the Banu Azd people when they came to pay tribute to him. It was said that every hunt with this stallion was successful, and when he was put to stud he founded the Arabian breed. Several other origin myths claim that the Arabian was created from the wind and stormclouds, including one where Allah says to the South Wind, “I want to make a creature of you. Condense.” The material condensed from the South Wind became the horse.

Assyrian horses on the so called Lachisch relief, from daughterofthewind.org

Arabians are one of the oldest human-developed breeds in the world. Horses with characteristics similar to the modern Arabian have been depicted in rock paintings and inscriptions in the Arabian Peninsula dating back 3,500 years. Ancient Egyptian art as far back as the 16th Century B.C. depicted horses with refined heads and tails with a high carriage. Horses with similar characteristics to the Arabian include the Marwari horse of India, the Barb of North Africa, and the Akhal-Teke of Turkmenistan.

The desert climate and culture greatly influenced the development of the Arabian breed. The desert environment needed a domesticated horse who would cooperate with humans to survive. Humans were the only source of food and water in some areas. Even hardy Arabian horses require more water than camels in order to live. If there was no water or pasture, the Bedouin would feed their horses camel’s milk and dates. A desert horse needs the ability to survive with little food, and must have anatomical traits that would compensate for the dry climate and extreme shifts of temperature between day and night. Arabians were bred to be war horses with speed, intelligence, and endurance. Mares were often preferred over stallions for raids requiring stealth, because they were quieter and less likely to give away the position of the raiding party. Because the prized horses were often brought inside the family tents at night to protect them from the weather, theft, and predators, a good disposition was necessary. Appearance was not required for the breed’s survival, but the Bedouin bred for refinement and beauty in their horses’ features as well as for their more practical traits. The Bedouin people knew the pedigrees of their best war mares in detail, including their accomplishments and victories, down through the maternal lines.

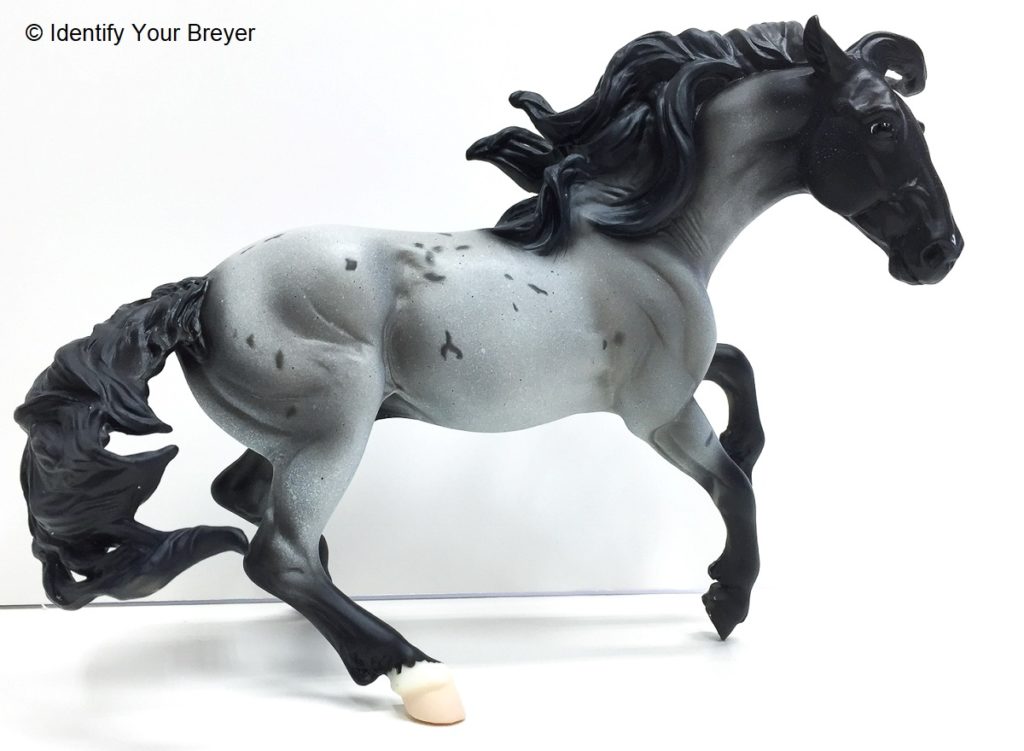

There is a misconception that because the Arabian is a small, refined breed of horse, that they are not strong. The Arabian has more dense bone than other breeds, short cannon bones, sound hooves, and a short, broad back, all of which give the horse a physical strength comparable to larger horses. Even a small Arabian can carry a heavier rider. In areas such as farm work, where a heavier horse is an advantage, the Arabian is not suitable because of their lighter weight and smaller stature. For most purposes, the Arabian is a strong and hardy light horse with the capability of carrying any type of rider in most equestrian sports.

Arabians are one of the few breeds where the United States Equestrian Federation rules allow children to show stallions in nearly all show ring classes. This is because of the Arabian’s naturally good disposition. For centuries, only horses with a good nature were allowed to reproduce, resulting in a breed with an overall good and willing disposition. Though the Arabian is considered a “hot-blooded” horse, unlike other high spirited breeds their intelligence enables quick learning and greater communication with their riders. The downside of this is that it is just as easy for the Arabian to learn bad habits as it is good ones, and they do not tolerate inept handlers or abusive training practices. Most Arabians are naturally inclined to cooperate with humans. When treated badly, however, they can become as nervous and anxious as any other horse, but they seldom become vicious unless severely abused.

The earliest horses with Arabian bloodlines to come to Europe probably did so indirectly, through Spain and France. Other Arabians arrived as spoils of war with knights returning from the Crusades. As heavily armored knights and their heavy war horses became obsolete, the Arabian horses and their descendants were used to develop faster and more agile light cavalry horses. Arabian horses also came to Europe when the Ottoman Turks sent 300,000 horsemen into Hungary in 1522, many of whom were riding pure-blooded Arabians. The Ottomans reached Vienna before they were stopped by the Polish and Hungarian armies. The horses were captured from the defeated Ottoman cavalry, and some of these animals provided foundation bloodstock for the major studs of eastern Europe.

As the use of light cavalry in warfare began to rise, the stamina and agility of Arabian horses gave an advantage to any army that had them. European monarchs began to support large breeding programs that crossed local stock with Arabian horses. European horse breeders also began to acquire Arabians through direct trade with the desert. By the late 1800’s, the Arabian as a pure breed of horse was under threat due to modern warfare, inbreeding, importing to Europe, and other problems that were reducing the horse population in the Bedouin tribes. Some Europeans began to collect the finest Arabian horses they could find in order to preserve the blood of the desert horse for future generations. The most famous collector of Arabians for the future was Lady Anne Blunt, the daughter of Ada Lovelace and granddaughter of Lord Byron.

World War I, the Russian Revolution, and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire destroyed many historic European stud farms. The Spanish Civil War and World War II also had a devastating impact on horse breeding throughout Europe. Many studs, and most records of breeding, were entirely lost. The Soviet Union and the United States obtained valuable Arabian horses as spoils of war. The Soviets had taken steps to protect their breeding stock, and using horses captured from Poland they were able to re-establish their breeding program soon after the end of World War II. Horses captured in Europe were brought to the United States, mostly to the Pomona U.S. Army Remount Station in California.

In America, the earliest Arabian horses arrived with Hernan Cortes in 1519. More horses followed with each Conquistador, missionary, and settler. Many horses escaped or were stolen and became the foundation stock for the American Mustang. Colonists from England brought horses of Arabian breeding to the Eastern Seaboard. One of George Washington’s horses during the American Revolutionary War was a gray half-Arabian named Blueskin. Other presidents also owned Arabian horses, including President Ulysses S. Grant, who obtained an Arabian stallion named Leopard and a Barb as gifts from the Sultan of Turkey.

One of the earliest American breeders of Arabian horses was A. Keene Richard. He crossed his Arabians with Thoroughbreds, but also bred pure Arabian horses. Unfortunately, his horses were lost during the Civil War and have no known purebred Arabian descendants today. Leopard is the only known stallion imported before 1888 who has known purebred descendants in America.

In 1908, the Arabian Horse Registry of America was established and recorded 71 animals. By 1994, the number of animals registered was half a million. There are more Arabian horses registered in North America today than in the rest of the world combined.

In the 1980’s, the Arabian horse became a popular status symbol. The horses were marketed in a similar fashion as fine art. Prices for Arabians went through the roof, with some people using the horses as tax shelters. A record-setting auction had a mare sell for 2.55 million dollars in 1984. A stallion sold at the same auction for 11 million dollars. The potential for profit on the horses led to over-breeding, and when the tax law was changed in 1986, the Arabian market was particularly vulnerable to over-saturation and inflated prices. The market soon collapsed, forcing many breeders into bankruptcy. Many pure-bred Arabians were sent to slaughter in the aftermath. The prices for Arabians recovered slowly after many breeders moved away from creating “living art” and began producing horses suited toward amateur owners and a variety of riding disciplines. As of 2013, there are more than 660,000 registered Arabians in the United States, the largest number of Arabians in any nation in the world. The second largest registry in the world is the Australian Arabian Horse Registry.

The genetic strength of the desert-bred Arabian horse has led to the bloodlines having a hand in the development of almost every modern light horse breed. This includes the Thoroughbred, Orlov Trotter, Morgan, American Saddlebred, Quarter Horse, Trakehner, Welsh Pony, Australian Stock Horse, Percheron, Appaloosa, and the Colorado Ranger Horse. Arabians are crossed with other breeds to add refinement, agility, beauty, and endurance. Some half-Arabian crosses, such as the Morab (Morgan-Arabian) are even popular enough to have their own breed registries.

There is some debate over the role the Arabian played in the development of other light horse breeds. DNA studies of multiple horse breeds suggest that, after the domestication of the horse, the location of the Middle East as the crossroads of the ancient world allowed the Oriental horse to spread through Europe and Asia. There is little doubt that humans crossed “oriental” blood to create other breeds of light riding horses. The only questions are at what point the “oriental” type horse could be called an “Arabian”, how much Arabian blood was mixed with local animals, and at what point in history. For some breeds of horse, such as the Thoroughbred, Arabian influence is documented in written stud books. For older breeds, the date of Arabian influx of breeding is more difficult to determine.

Arabians are intelligent, willing, and versatile horses that compete today in many equestrian disciplines. Horse racing, saddle seat, Western pleasure, hunt seat, dressage, show jumping, cutting, reining, endurance riding, eventing, and youth events all see Arabian participants. They are used for pleasure riding, trail riding, and working horses. The Arabian dominates the sport of Endurance riding thanks to their superior stamina. They are the leading breeds in competitions such as the Tevis Cup, where they can cover up to 100 miles in a day.

Series of horse shows specifically for Arabians and half-Arabians exist in America, Canada, Great Britain, France, Spain, Poland, and the United Arab Emirates. In North America, the Arabian Horse Association’s “sport horse” events draw up to 2000 entries. This competition sees Arabian and part-Arabian horses performing in hunter, jumper, dressage, combined driving, and sport horse under saddle and in hand classes.

Purebred Arabians have also excelled in open events against other breeds. They have won against other breeds in Refined Cow Horse, cutting horse, show jumping, and show hunter competitions. A purebred Arabian competed on the Brazilian eventing team in the 2004 Athens Olympics. Arabians have won Olympic medals in dressage and show jumping as well.

Arabians have been popular in movies dating back to the silent film era when Rudolph Valentino rode the Arabian stallion Jadaan in 1926’s “Son of the Sheik”. They have been seen in many films, including The Black Stallion, as well as Hidalgo and Ben-Hur. They are popular mascots for sports teams. Arabians are also used in search and rescue teams and for police work, as polo horses, in circuses, therapeutic horse riding programs, and on guest ranches.

The Arabian is a breed that has had influence all over the world. From the tents of the Bedouin people who fed their prized mares dates and camel’s milk, to the personal mounts of kings and Presidents, to the Olympic games. They are truly a versatile breed with intelligence and a willing disposition.

Find out more about the Arabian breed at the Arabian Horse Association’s website at https://www.arabianhorses.org/